Dogs are dying from harmful algae in lakes and ponds. So what does that mean for your drinking water?

Harmful Blue-Green Algae Blooms in fresh water are toxic, and multiply in hot weather.

Warm summer weather encourages us to head to nearby lakes and ponds for a swim, and sometimes we bring our family dog along. But recently, these outings have turned deadly for man’s best friend.

Alarming stories of dogs dying after swimming in water contaminated with harmful algal blooms have been widely circulated recently. The dogs have perished quickly, sometimes as fast as an hour after swimming.

Human exposure to these toxins can result in adverse health effects including gastroenteritis, liver, and kidney damage. Many public utilities use surface water sources, such as rivers and lakes, as drinking water supplies. Even some ground water sources are under the direct influence of surface water.

What is the local impact of Harmful Algal Blooms (HAB)? And how concerned should we be about our water supplies?

What are HABs?

Surface water runoff from the shore, usually after substantial rain events, thrust an excess of nutrients into surface waters. These nutrients, mixed with high temperatures, cause algae to grow excessively. These algal colonies eat up the oxygen supply as they grow and decay, which smothers aquatic life. They usually discolor the water and form large smelly piles on the surface.

However, not all algae is toxic.

HABs occur when colonies of algae grow out of control and produce toxic effects on people and marine life. Some freshwater algal blooms produce highly potent toxins, known as cyanotoxins. Blue-green algae, or cyanobacteria, are frequently found in freshwater systems. These cyanotoxins can pose a risk to human health (US EPA 2014a).

These cyanotoxins are produced and contained within cyanobacterial cells (intracellular). According to the US-EPA, the release of these toxins in an algal bloom into the surrounding water occurs mostly during cell death and lysis (i.e., cell rupture) as opposed to continuous excretion from the cyanobacterial cells. However, some cyanobacteria species are capable of releasing toxins (extracellular) into the water without cell rupture or death.

Drinking Water Treatment

Knowing we have many clients that use surface waters as sources for public drinking water consumption, we wanted to know how they are managing this recent spike of HAB reports.

We reached out to a local expert, Matt Walborn of Western Berks Water Authority, who serves high quality drinking water to more than 50,000 Berks County residents. The utility uses Blue Marsh Lake as a water source for some of its customers.

“We are well equipped to remove any HABs that may exist with three particular stages of our treatment systems: our Dissolved Air Flotation (DAF), our Powdered Activated Carbon (PAC), and effective oxidation using chlorine disinfection,” said Mr. Walborn. “Whether intracellular or extracellular HABs existed, we would be able to effectively treat for it.”

Western Berks Water Authority works closely with the US Army Corps of Engineers, who manages Blue Marsh Lake and actively communicates with them to understand the health of the water supply.

The US Army Corps of Engineers has been testing Blue Marsh for HABs weekly.

Acceptable Levels of Cyanotoxins in Drinking Water

There are no “acceptable levels” established for cyanotoxin consumption in the Safe Drinking Water Act. But in 2015 the EPA did release a “Health Advisory” (HA) for Cyanobacteral Toxins, which stops short of regulating the contaminant for testing. This HA established non-regulatory contaminant technical guidance, including levels of harmful consumption and health effects. They also published guidance for Public Water Systems to manage cyanotoxins in drinking water, including providing treatment recommendations. The methods of treatment used by Western Berks Water Authority are included in the USEPA’s recommendations for cyanotoxin removal.

Testing for Cyanotoxins

Cyanotoxin contaminants are on the Contaminant Candidate List (CCL) for possible addition to the Safe Drinking Water Act.

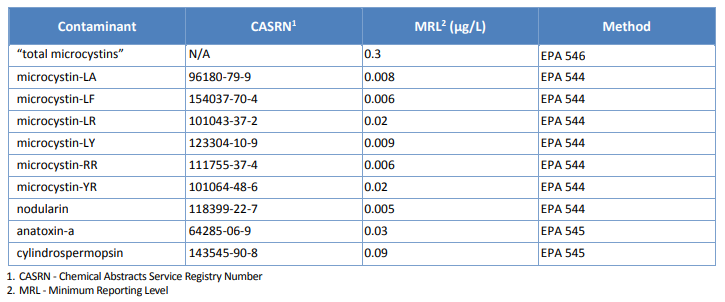

To understand the scope of cyanotoxin contamination in public water supplies, the USEPA is currently requiring water supplies that serve more than 10,000 people to test for nine cyanotoxins and one cyanotoxin group as a part of The Fourth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR4). Every five years the EPA issues a new list of contaminants to be monitored to establish if they should be added to the Safe Drinking Water Act’s list of required monitoring. In the meantime, the HA is the only guidance EPA has given.

Cyanotoxin samples are collected after treatment and disinfection, but before the water enters the distribution system, or at the Entry Point to the Distribution System. There are three approved methods for testing.